History of Radio in Alabama

THE HISTORY OF RADIO BROADCASTING AT AUBURN UNIVERSITY (1912-1961)

James H. Rosene

A Thesis Submitted to

the Graduate Faculty of Auburn University

in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the

Degree of Master of Arts

Auburn, Alabama

December 12, 1968

From Harry D. Butler; author, Alabama' First Radio Stations 1920-1930 212 Adele Street, Rainbow City, AL +256-442-7895

VITA

James H, Rosene, son of Walter and Kathryn (Giles) Rosene, was born in Birmingham, Alabama, on June16, 1940. He was educated in the public schools of Gadsden, Alabama. After being graduated from Gadsden High School in June, 1958, he entered Auburn University in September, 1958, and received the degree of Bachelor of Arts in March, 1962. His major was English Journalism. He entered the United States Navy in June, 1962, and served in the Atlantic and Mediterranean Fleets for three years. He was discharged from the Navy, as Lieutenant (Junior Grade), November, 1966. In January, 1967, he re-entered Auburn University as a graduate student in Speech. He married Jean Dee, daughter of Charles and Mary Louise (Sherman) Fennelle, in January, 1965.

THESIS ABSTRACT

THE HISTORY OF RADIO BROADCASTING AT AUBURN

UNIVERSITY (1912-1961)

James M. Rosene

Master of Arts, December 12, 1968

(B.A., Auburn University, 1963)

128 Typed Pages

Directed by William S. Smith

In 1912, Miller Reese Hutchinson, an Auburn alumni, donated a primitive spark gap transmitter to the Engineering Department at Auburn. The small set marked the beginning of over two decades of educational broadcasting. Through the following years, studios and equipment would be shifted about the campus, finally coming to rest on the top floor of the Protective Life Building in Birmingham, Alabama.

The history of radio broadcasting at Auburn University is presented through a study of the development of various transmitting sets at Auburn and Birmingham, the personnel who operated those sets and the difficulties encountered. A comparison is drawn between Auburn University's venture into educational radiobroadcasting and the failure of educational radio broadcasting in general.

The study is specifically designed to be a source of reference for undergraduates and graduates in radio-television courses at Auburn University.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

To Mr. V. C. McIlvaine and Mr. P. O. Davis I express special thanks for providing me with valuable information on their part in WAPI's history. Without their help, my task would have been far more difficult. Equal gratitude extends to the many others who wrote stimulating letters describing their part in Auburn's radio history. For help in finding some of the more important primary material I am indebted to the staff of the Alabama Department of Archives and History and Mrs. Carolyn J. Dixon of the Department of Archives, Auburn University. I would like to express particular thanks to my wife, indefatigable reader of proofs and impeccable typist, for her many improvements and corrections.

Table of Contents

List of Figures ix

I. INTRODUCTION 1

II. THE EARLY YEARS. 12

The Hutchinson Set

The Birmingham News Gift

The Alabama Power Gift

III. THE BIRTH OF WAPI 35

The Decision to Stay in Broadcasting

Programing in the Twenties

The Difficulties at Auburn

IV. Broadcasting in Birmingham 58

WAPI is moved

An Alliance Among Schools

The Difficulties at Birmingham

V. FURTHER DEVELOPMENTS AND SALE 79

Th1e Governor and Broadcasting

The Leasings

Commercial Developments

VI. WAPI IN RETROSPECT 91

BIBLIOGRAPHY 99

APPENDICES 105

A. Memorandum of Agreement Between the Alabama Polytechnic Institute and the City of Birmingham, Alabama 106

B. Memorandum of Agreement Between Alabama Polytechnic Institute, the University of Alabama and Alabama College 110

C. Agreement Between the Board of Control of Radio Broadcasting Station and WAPI and WAPI Broadcasting Corporation `114

LIST OF FIGURES

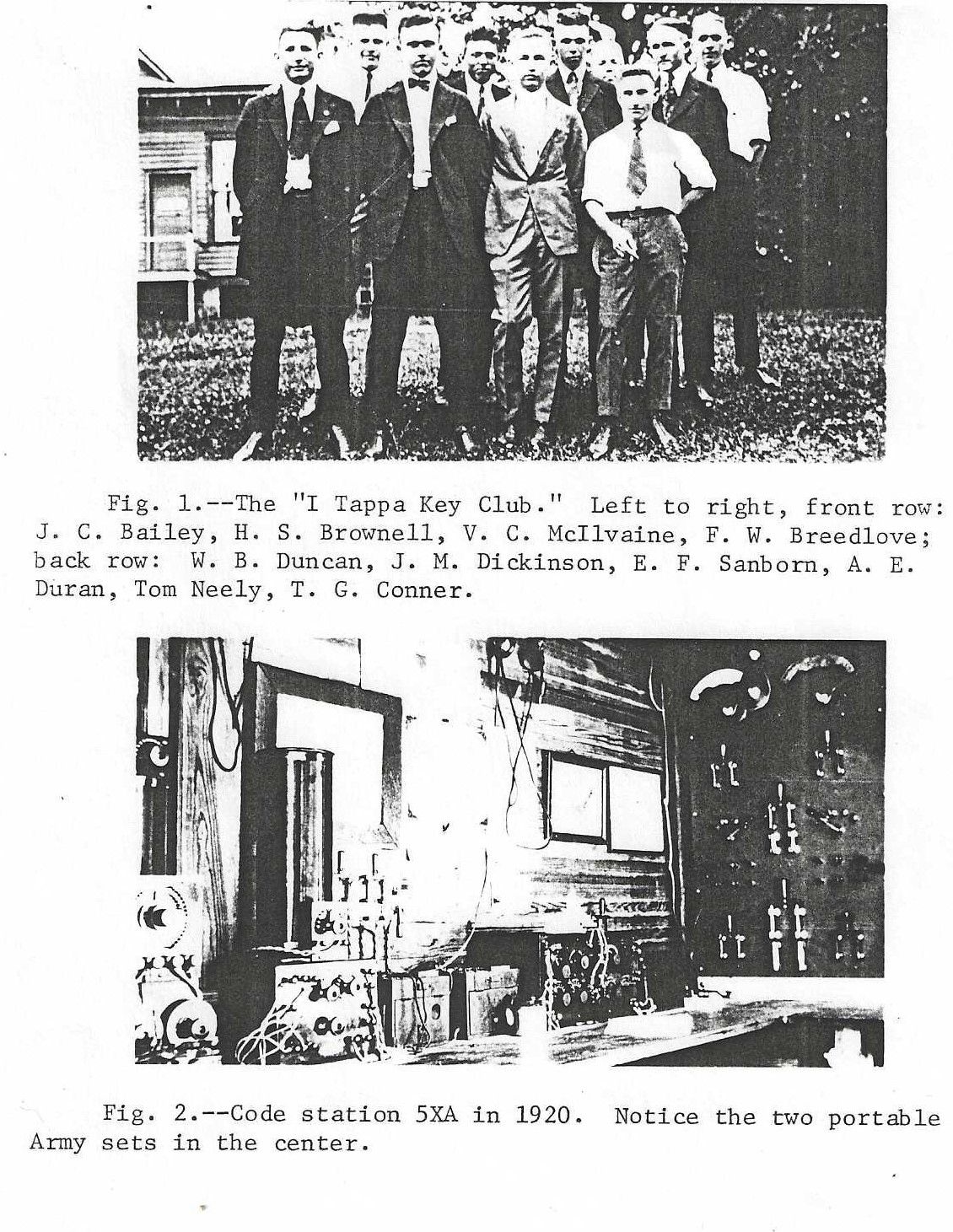

1. The "I Tappa Key Club" 18

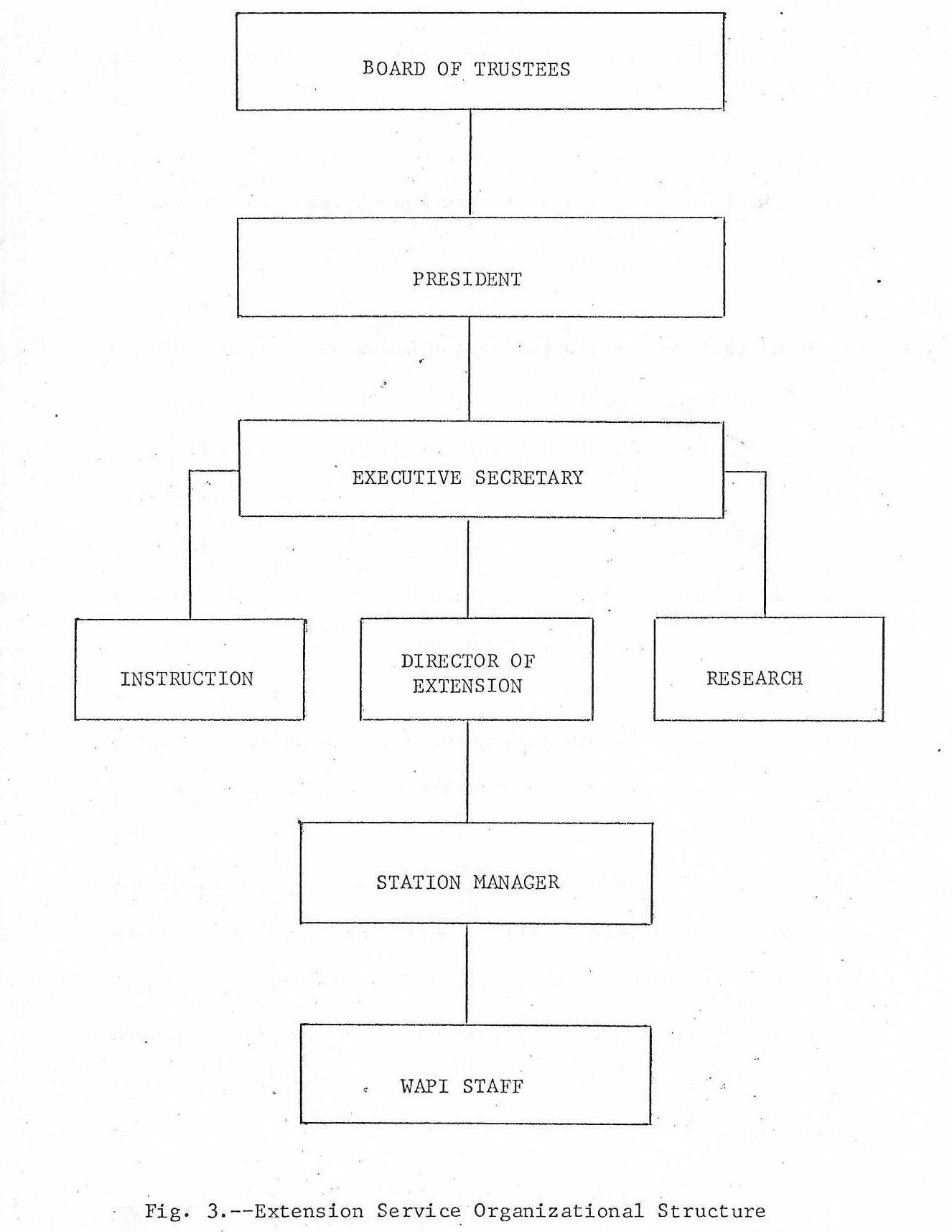

2. Code Station 5XA in 1920. 18

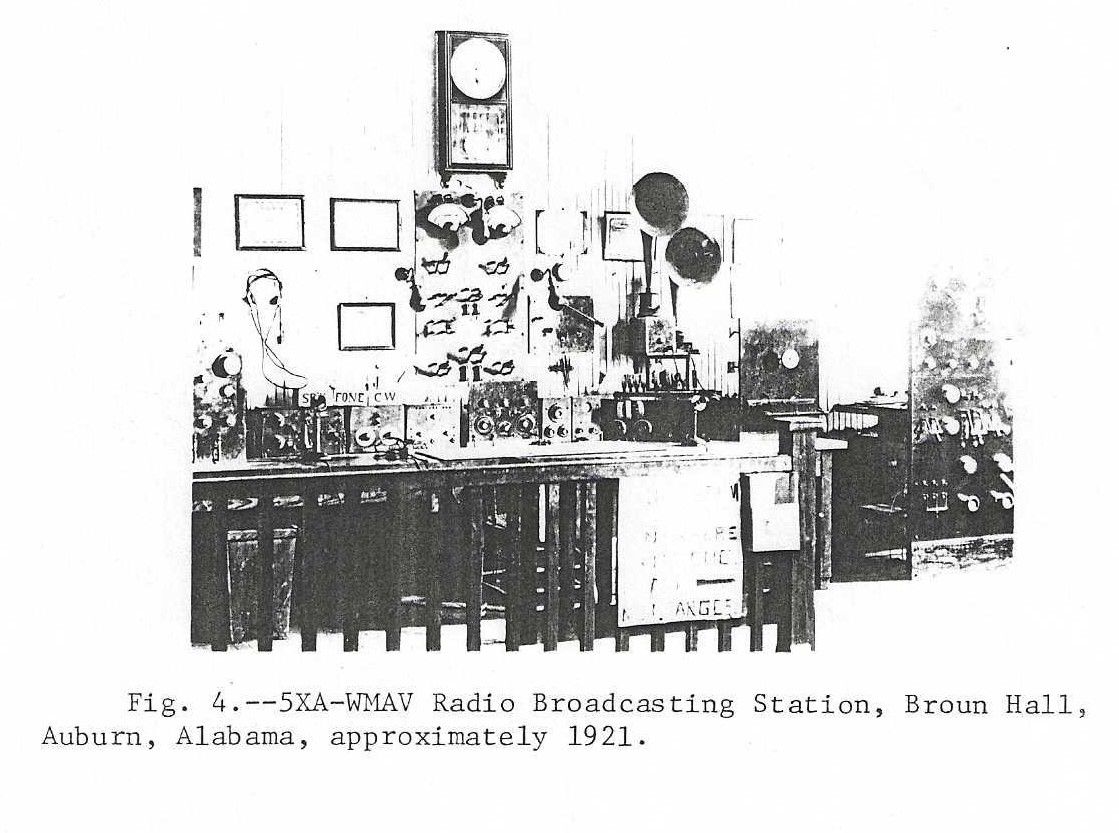

3. Extension Service Organizational Structure 22

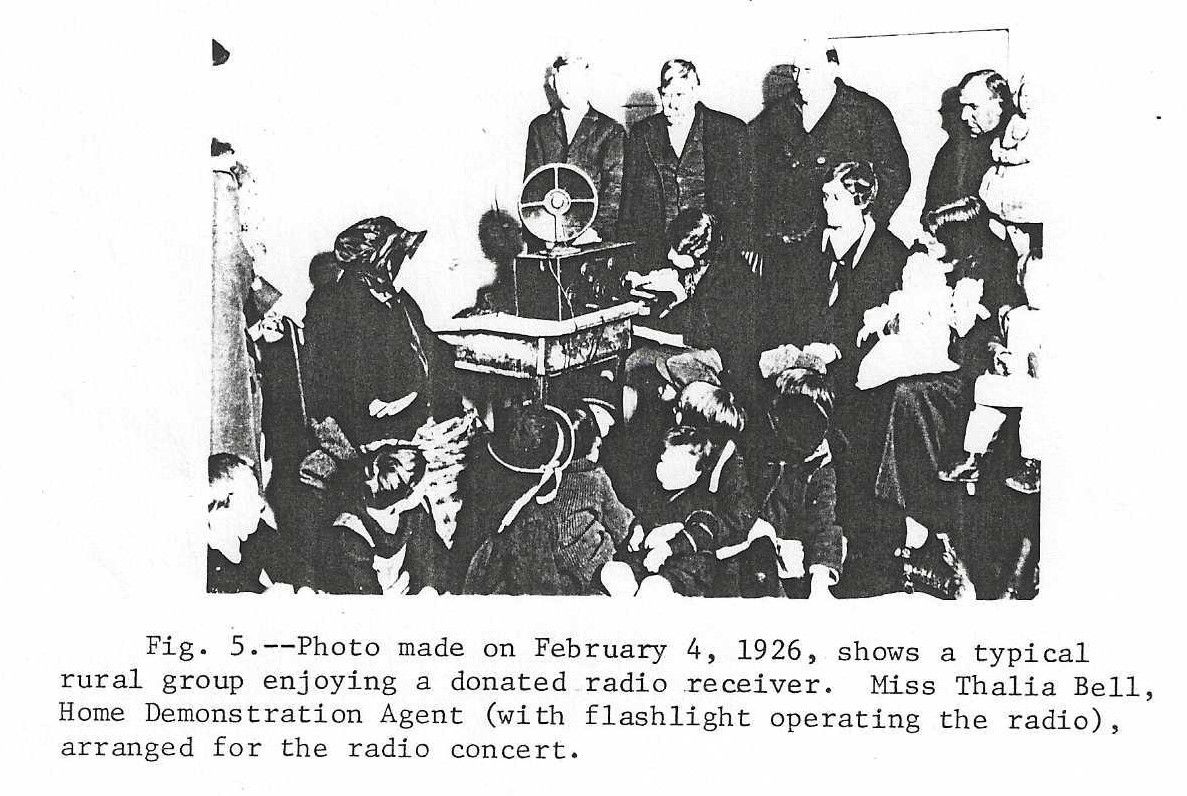

4. 5XA-WMAV Radio Broadcasting Station, Broun Hall, Auburn, Alabama, approximately 1921 24

5. Rural People Enjoying a Donated Radio Receiver, Photo Made on February 4, 1926. 29

6. WAPI Transmitter Shack at Auburn in 1926. 38

7. Two 200-Foot Towers of WAPI in Auburn. 38

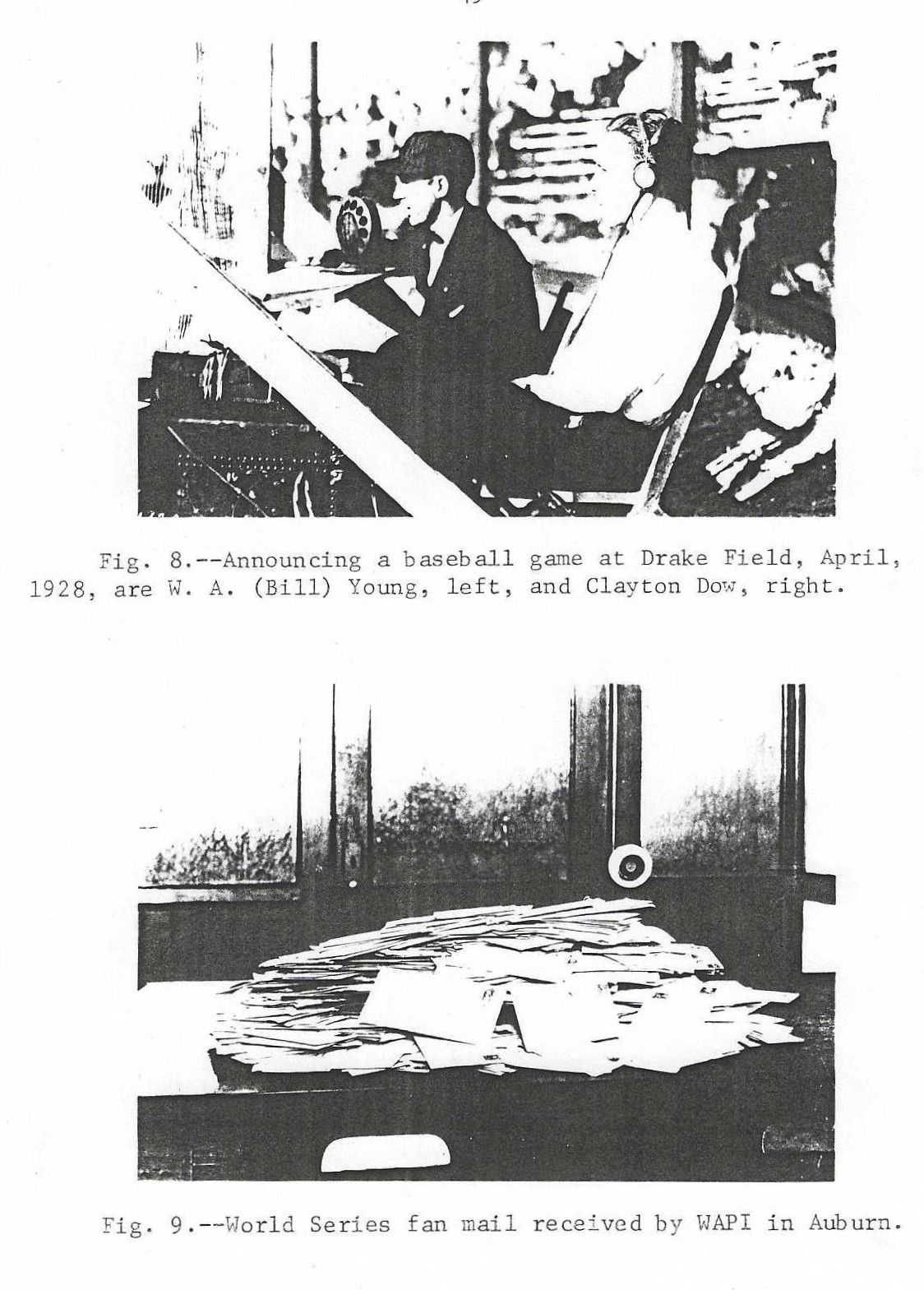

8. W. A. Young and Clayton Dow Announcing a Baseball Game at Drake Field, April, 1928 49

9. World Series Fan Mail Received by WAPI in Auburn. 49

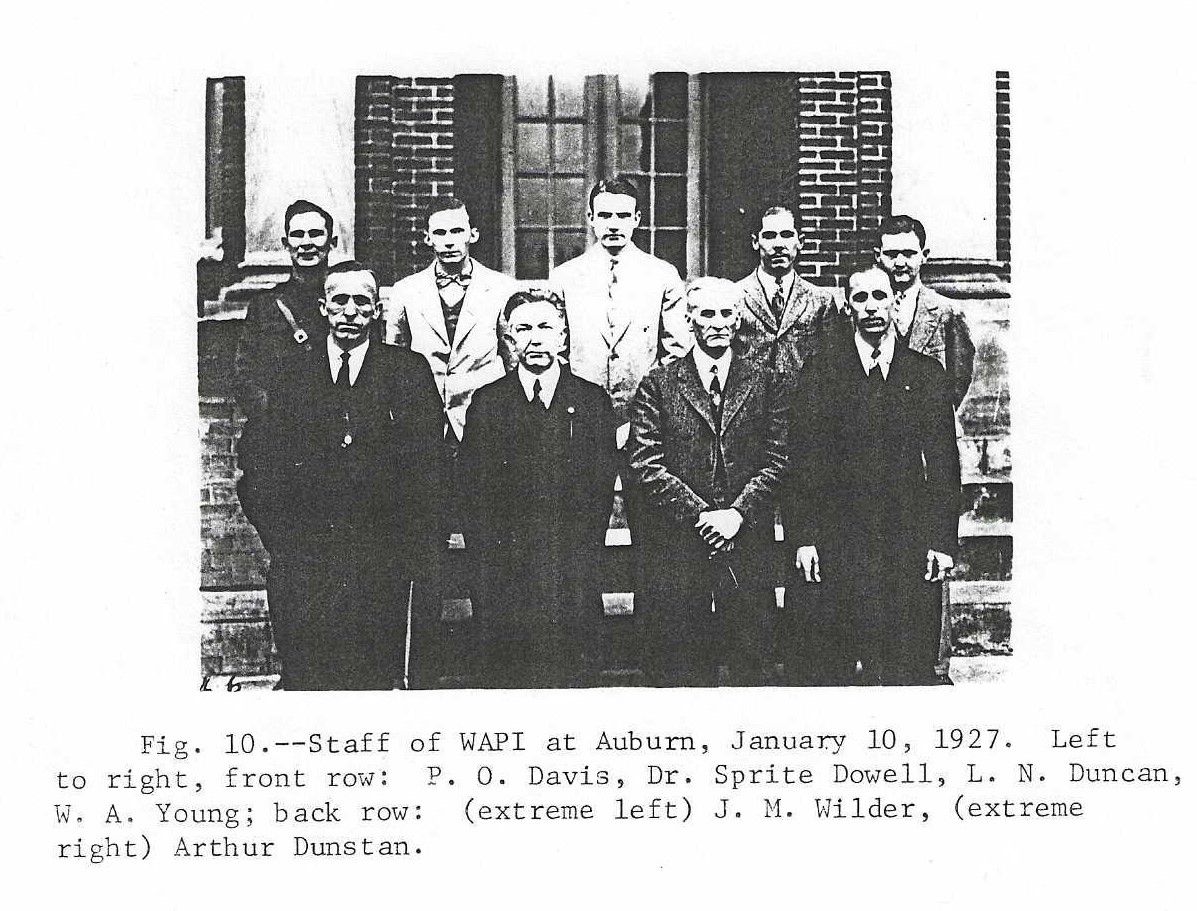

10. Staff of WAPI at Auburn, January 10, 1927 52

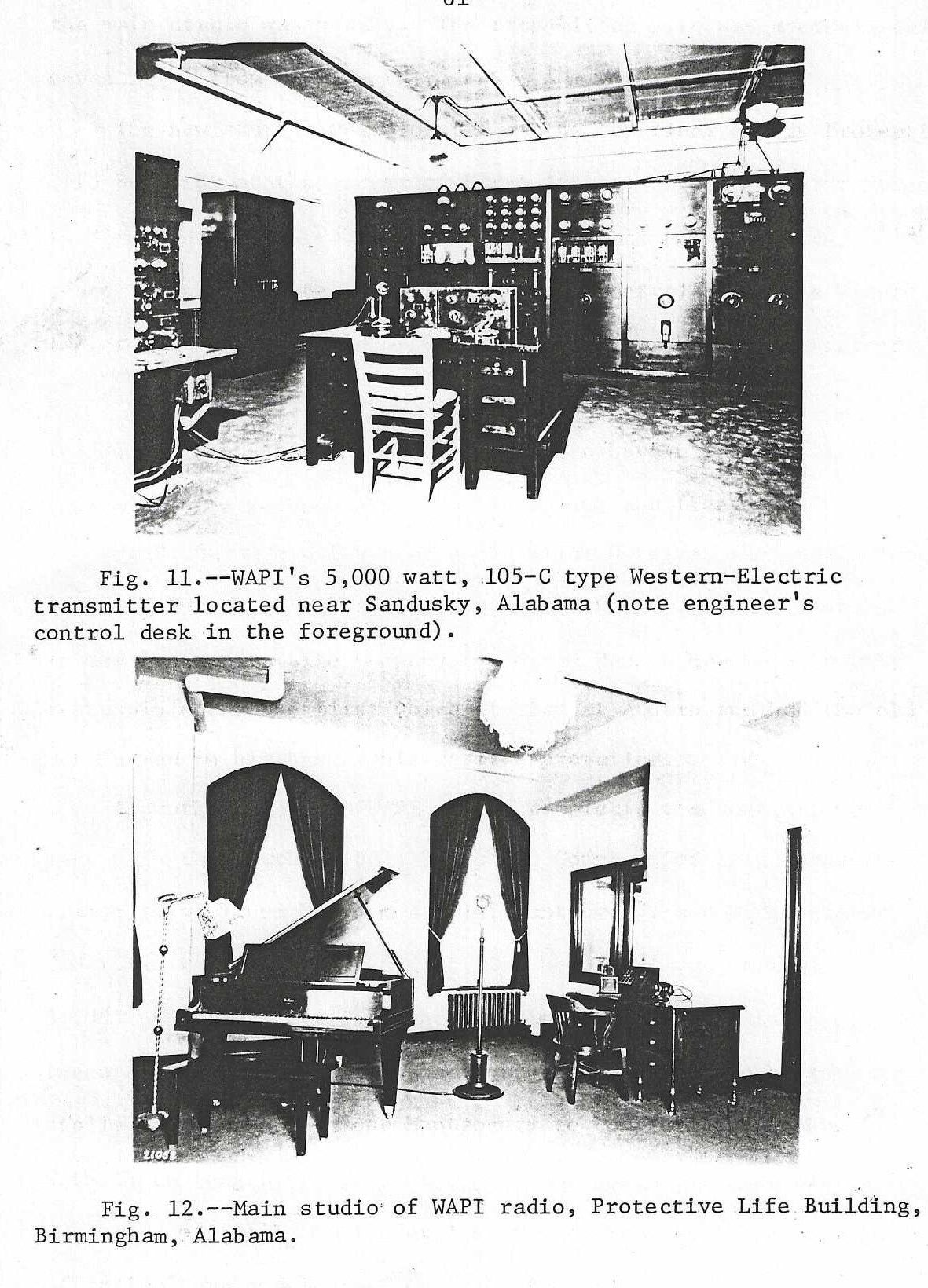

11. WAPI's 5,000Watt, 105-C Type Western-Electric Transmitter Located Near Sandusky, Alabama. 61

12. Main Studio of WAPI Radio, Protective Life Building, Birmingham, Alabama 61

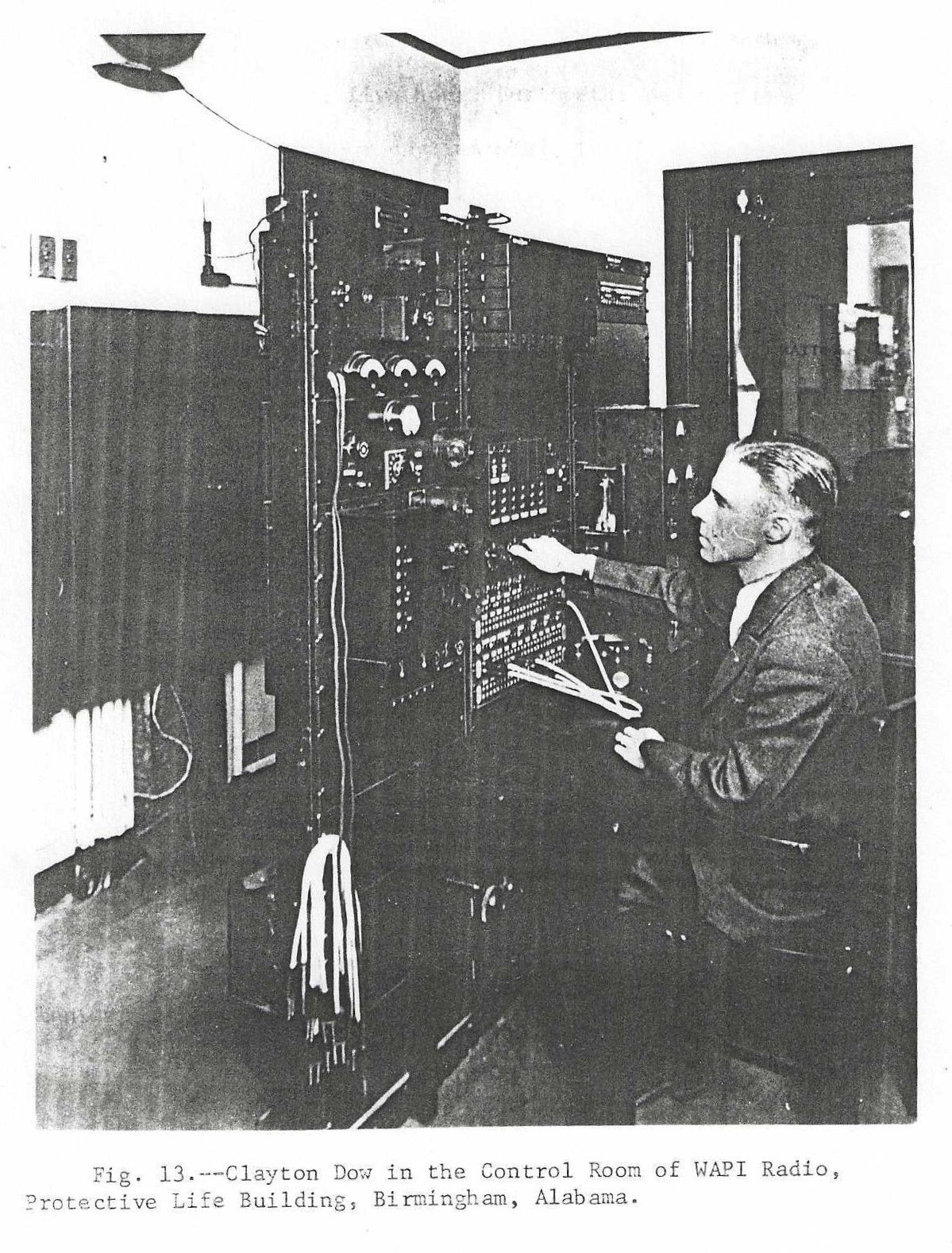

13. Clayton Dow in the Control Room of WAPI Radio, Protective Life Building, Birmingham, Alabama 63

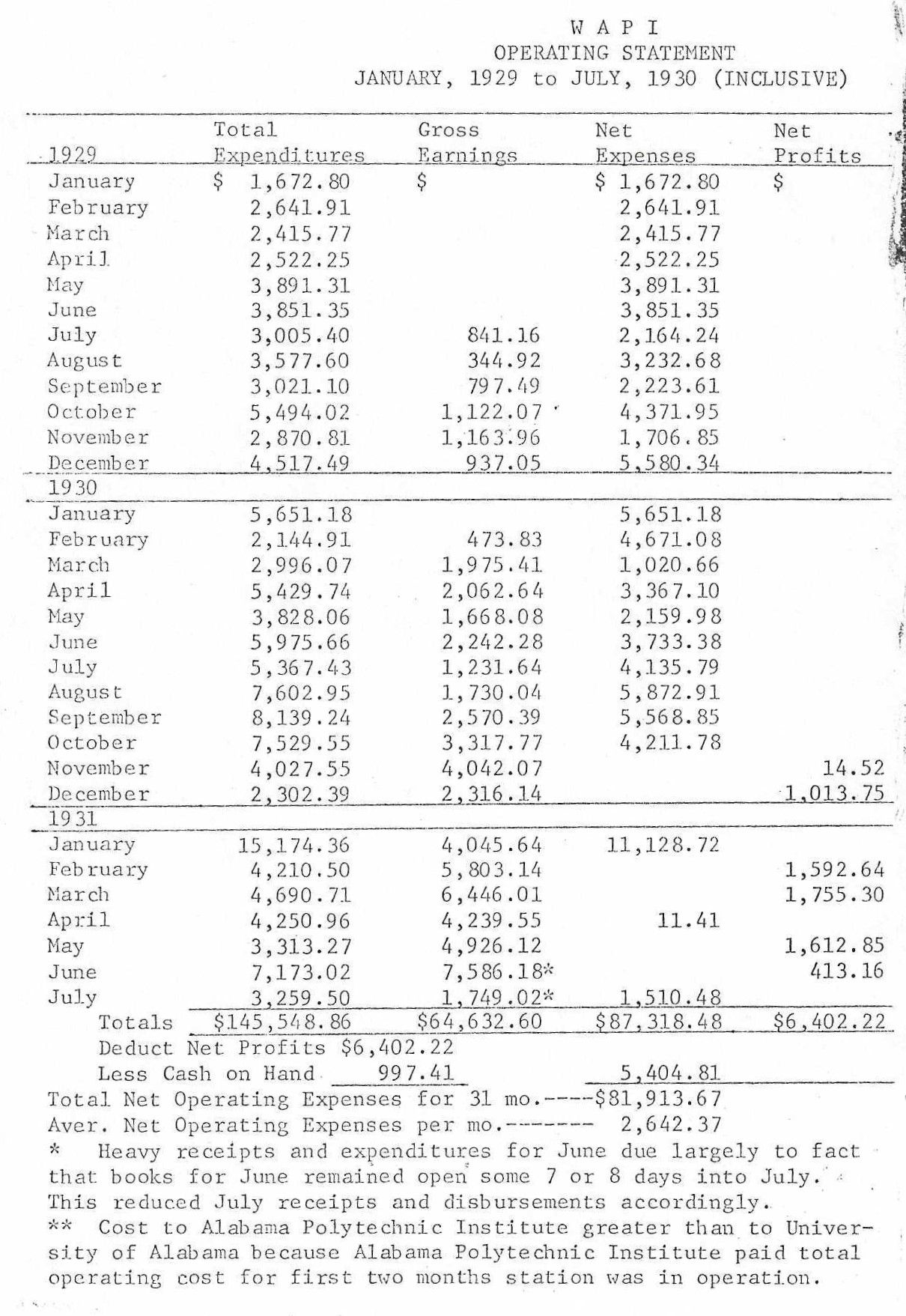

14. WAPI Operating Statement, January, 1929, to July 1930 74

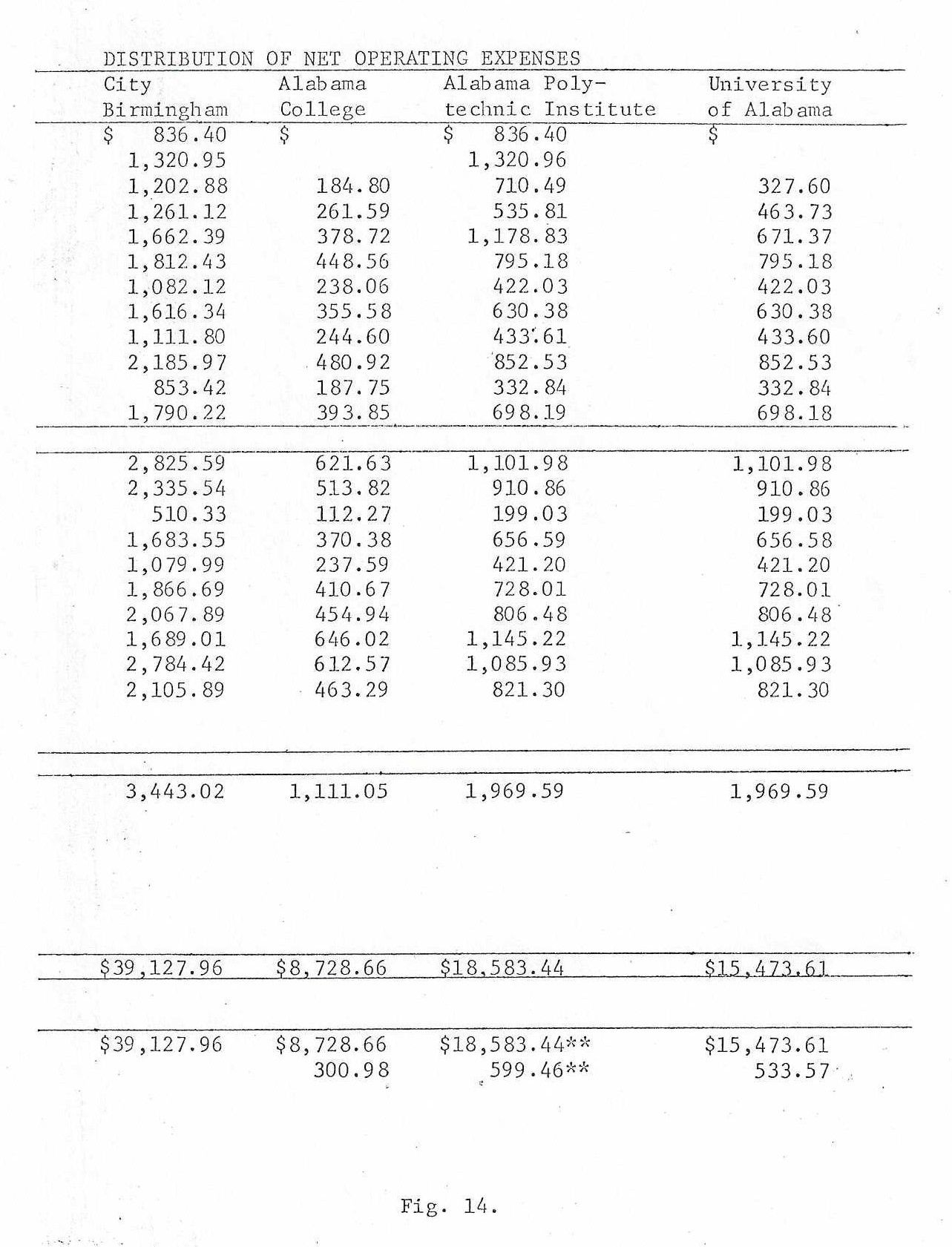

15. · Governor Bibb Graves Shown with Atwater-Kent Model 45 Radio Receiver 80

16. WAPI Radio's Coverage at 50,000 Watts of Power

I. INTRODUCTION

At American universities and colleges enterprising physics and electrical engineering departments had experimented with wireless telegraphy for many years prior to the development of practical voice broadcasting.

When Congress passed the pioneering Radio Act of 1912, many educational institutions quickly complied by· filing for licenses from the Department of Commerce. Since there were few qualifications to be met, getting a license was a simple procedure. Some of the schools to immediately· respond to the Act were the University of Arkansas, Cornell, Dartmouth, University of Iowa, Ohio State, Tulane, Villanova; and the University of W1scons1n. Auburn University licensed and began operating its own wireless station in 1913. Other schools followed, and it seemed as though they all would be in a position to dominate voice broadcasting when it appeared in the twenties.

From 1912 to 1920 the ether was filled with the coded messages of the Marconi Company, the United States Navy, and a few enthusiastic hams. During these early years, an occasional operator was startled to hear a human voice crackle in his earphones, but usually he was lulled by the syncopated buzz of Morse Code transmitted by primitive, homemade spark gap transmitters and received by equally primitive crystal detectors.

During World War I, the United States Navy took over all wireless broadcasting and the hams were required to disassemble their transmitters. The consolidation of all radio technology into the hands of the Navy and the pressures of war created rapid advances in voice broadcasting. By war's end the hams, including those at American universities and colleges, were anxious to get on the air again. The transition to primitive voice broad casting was relatively simple and soon many schools had gone over to, the new technique. Programs and other services to listeners quickly followed.

In 1920 KDKA in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, was the only station in the United States licensed to provide a regular broad casting service. The Westinghouse East Pittsburgh factory converted a radio telegraph transmitter for radio-telephony, mounted it in a shack on the roof of a plant building and began broadcasting on November 2, 1920.

The following year only a few more stations were licensed in the new medium, but in 1922 radio broadcasting suddenly exploded in to an unqualified rush for slots in the frequency spectrum. In that year, a phenomenal 500 stations were licensed. Of course, in such a new and untried field, there would be a variety of interests, owners, and speculators. By January of 1923 , seventy two universities, colleges, and schools held broadcasting licenses along with a generous sampling of newspapers, department stores, and religious organizations. There were even a few city governments, auto dealers, theatres and banks licensed. All were eager to experiment with the novel and exciting scientific toy. Technically, the educational institutions held the advantage since all colleges with engineering departments had talented students who were anxious to build transmitting or receiving apparatus.

The schools began broadcasting educational programs immediately. In 1922 New York University, Columbia, and Tufts originated extension courses on the air. The mid-western schools of Wisconsin and Michigan State began programming crop and weather reports for farmers. There was no reason why other schools couldn't provide similar services.

The advantages of radio broadcasting were obvious. With radio the university could reach far beyond the classroom, campus, or extension service. Here was direct access to the home. Now the housewife could work toward that college diploma without leaving the children. Here was access to the farmer. Radio could do the work of hundreds of agricultural extension personnel. Broadcast radio could pass along the market prices for farm products that very day, warn of impending weather conditions, and explain the latest farming tips. The problem of rural isolation would be solved.

Radio could go far beyond the traditional approaches to education. Now there could be dramatic re-enactments of history with realistic sound effects instead of dull lectures. Famous educator sand newsmakers would be available to all. Radio would bring the events as they occurred; it would conquer time. The possibilities seemed unlimited. No doubt many educators envisioned scenes of family groups gathered about their radio receivers, enjoying the universities' cultural and educational offerings.

Yet, by the end of the twenties, it became clear that educational broadcasting was largely unsuccessful. Charles A. Siepmann, in his book Radio's Second Chance, summed up the failure by declaring, "The story of educational radio stations is, at worst, one of sheer professional incompetence, at best, it is the record of a courageous struggle against almost hopeless odds." 5 Siepmann's comment starkly simplifies the extremes of a complex and tragic tale of few triumphs and endless defeats.

By 1936, 202 educational licenses had been granted, most of them before 1927. However, during the same period, 164 of these stations ceased operation or sold out to commercial interests. Fifty of the 164 lasted less than one year. Only fifty-five lasted for three years or more. 6 The thinning out process continued another ten years.

Llewellyn White reported in his book, The American Radio, that:

At the end of 1946,29 standard (AH)broadcasting stations were licensed to educational institutions; of these, 9 were commercial, 5 of them affiliated with networks. 10 of them non-commercial, were permitted to use 5,000 watts or more power; but, of these, only two could broadcast between sunset and sunrise, local time. 7

What happened to educational broadcasting? What caused such a promising venture to shrink to insignificance? How could hundreds of educational stations become only a handful? At the risk of oversimplification, it is necessary to point out that all radio has certain inherent shortcomings. The audience is forced to listen blind, a problem which television solved in the late forties and fifties. The human voice and sound effects can do just so much in presenting material or establishing mood. The remainder is left to the visualization powers of the listener. Radio drama became a popular art form because it stimulated this visualization process. However, visualization of philosophy or physics based on a voice and sound effects was another matter.

Broadcasting was, and still is, one-way in nature. Normally, there is no direct feedback from the audience. Again, in a radio drama or even a quiz show, an immediate audience response was unnecessary; but traditionally students had always been able to ask questions, the radio student could not.

Radio quickly became the slave of time, the advent of network broadcasting required strict adherence to a program schedule. Non-commercial radio, in order to gain and hold any audience of its own, had to adhere to a similar schedule. Thus, programs had to fit into strict time limits regardless of subject matter. 6 Schedules also required that the listener be on call, no matter how inconvenienced.

Early radio had only the most primitive of audience sampling methods. Stations merely asked their listeners to send a postcard if they could hear the broadcast. Judging the circumstances and intelligence of the audience with such a primitive technique was impossible. To educational broadcasting an accurate estimation of audience composition was essential.

Upon examination of the shortcomings attributed specifically to educational broadcasting, one finds that most authorities have blamed economics in general and three groups in particular: the commercial broadcasters, the United States Government, and the educators themselves.

The commercial broadcasters financed their stations through advertising. August 28, 1922, is the date considered by many to mark the debut of American broadcast commercialism. On that day at 5:00 p.m. WEAF, the famous American Telephone and Telegraph station, leased ten minutes of air time to the Queensboro Corporation to promote the sale of apartments in Jackson Heights, New York. 8 From this modest, in direct appeal, radio advertising grew to the high profits and hard sell of the thirties.

The educational stations remained dependent upon state and university funds, with occasional contributions and gifts from other sources. 9 Almost from the very beginning, they found themselves at a financial disadvantage.

With strong financial backing, the commercial broadcasters were able to bring overwhelming pressure to bear against the educational broadcasters. With so many stations clammering for frequencies, there were countless hearings before the Federal Radio Commission and later the Federal Communications Commission. The commercial stations were able to finance these often extended hearings and hire qualified lawyers to present their cases; the educational stations could not. As a result, the Commission tended to rule in favor of the commercial stations. In addition to frequency allocations, the Commissions often ruled against the educators on matters of channel interference, frequency shifts, time sharing, and limitation of broadcasting hours.10 All of these were common technical problems of the twenties.

While the institutions were interested in providing a service to a relatively small portion of the population, the quest for profits caused the commercial broadcaster to seek wider audiences. It was a classic case of opposing goals. The commercial station, maneuvering from a superior economic position, forced their heavy-handed victory.

Authorities have condemned the government for allowing commercial broadcasters to put so much economic pressure on the schools. Educational stations were licensed along with the commercial ones. Neither side, at least on paper, was given any privileges. Yet, from a financial standpoint, it is clear that the educational stations needed some kind of protection.

The Radio Act of 1927 put a great burden on some institutions. By that time radio technology had become relatively so sophisticated, but many schools were struggling along with equipment they had used from the beginning. The Act placed equipment standards upon broadcasters, and stations were required to stay within restrictive power and frequency limits. Many educational stations with their obsolete transmitters could not meet these requirements. 12 Unable to finance new equipment, they gave up their licenses. Many feel these technical standards could have been temporarily waived for the schools.

Finally, the educators must share some of the blame. In 1920, institutions were not prepared to finance the dreams of a few faculty members and students. As the equipment standards went up, substantial financial support was essential. Far too often it never came. As the novelty of radio wore off, program standards also became a factor. Listeners were no longer content with whatever they could tune in. Educational broadcasts became boring, long, and unimaginative. With limited funds, station directors and script writers were either very poor or very inexperiencedThere was resistance to a new medium that called for considerable deviation from traditional teaching methods. An excellent lecturer in the classroom was often found to be something else on radio.

One other factor in the failure of educational broadcasting which can't be attributed to any particular group can be described as "entertainment fixation." As commercialism and the quest for audiences grew, the listeners began thinking of radio strictly as entertainment. The commercial broadcasters realized that they must appeal to the widest possible audience to be successful. They created programs that were "fun." "Amos 'n Andy," "Jack Armstrong," and even "The Whiz Kids" were "fun" programs. All entertainment became "fun." The educators, not particularly interested in audience size, wanted to propagate information. Education became "information" and "information" wasn't much "fun." Most of radio became a relaxing, uninvolved diversion. Educational stations, as exceptions, found themselves in a hostile environment.

The history of radio broadcasting at Auburn University typifies the failure of educational radio in the United States. Auburn was plagued by all the difficulties ever faced by an educational station. The University administrators and station managers struggled with a commercial station over shared time. They were miffed by an unsympathetic Federal Radio Commission, and they could never solve the problems of financial 10 support. There were miscalculations; there were blunders; but despite them all, Auburn deserves the highest tribute. This is truly "the record of a courageous struggle against almost hopeless odds."

FOOTNOTES

1 Erik Barnouw, A Tower in Babel (New York: Oxford University Press, 1966), I, 32.

2 Ibid., p. 69.

3 Sydney W. Head, Broadcasting in America (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co., 1956), p. 109.

3 Llewellyn White, The American Radio (Chicago University of Chicago Press, 1947), p. 101

5 Charles A. Siepmann, Radio's Second Chance (Boston: Little, Brown and Co., 1946), p. 270.

6 White, p. 101.

7 Ibid., p. 102.

8 Barnouw, p. 110.

9 Ferris Tyler, An Appraisal of Radio Broadcasting in the Land-Grant Colleges and State Universities (Washington: National Committee on Education by Radio, 1933), p. 12.

10 White, pp. 102-104.

11 Ibid., p. 110. White explains that this mistake was not made with FM and television. In both cases, certain specified educational channels were set aside for the exclusive use of non commercial broadcasters. The disaster of AM broadcasting was sufficient cause to prompt the FCC to belated action.

12 Ibid. , p. 103.

13 Siepmann, p.271.

14 Ibid.,

15 Ibid., p.270

II. THE EARLY YEARS

The Hutchinson Set

Disaster brought radio into prominence in 1912. Frantic dots and dashes from the sinking Titanic had pricked the public interest, and suddenly those curious wireless sets had become useful. Congress quickly passed a radio act to license and regulate stations. By adopting the "SOS" signal proposed at the Berlin Convention of 1906 and by assigning the specific many wave lengths to be used, Congress hoped that the new legislation would save lives at sea. 1 Of course, on land, wireless could never hope to replace Morse's telegraph which had been such a faithful servant to the nation for decades.

Despite all the public interest, in 1912 naval disasters and wireless sets were far, far away from tiny, land-locked Auburn. Only the professors and students in electrical engineering and physics understood how the unusual gadgets worked. Most of them considered wireless impractical overland. Other areas of study seemed eminently . In January, when a famous alumnus donated a wireless set to the Electrical Engineering Department, only a handful of people saw any value in the new device.

The alumnus was Miller Reese Hutchinson, electrical engineer, inventor, and assistant to Thomas A. Edison. 2 The set was small and, of course, very crude; but in 1912, it was the very latest design. The set had a spark transmitter with straight gap and plate glass condenser. The receiver was a crystal detector. 3 A 150-foot steel pipe mast was erected near the east end Broun Hall, and an antenna was strung from there to the second floor of Broun where the set was located. 4 There is some evidence that Hutchinson left his post at the Edison Laboratories in Orange, New Jersey, and traveled to Auburn to supervise the installation himself. 5

There is no doubt that he came to Auburn the following year to attend an elaborate alumni homecoming celebration which had been arranged to coincide with June graduation. During this event on Tuesday, June 2, 1913, Hutchinson formally dedicated the set. 6 In his speech, he read the first message transmitted with the new apparatus.

Mr. Thomas A. Edison, Orange, N.J. :

This wireless formally christens the two-and-a-half kilo-watt apparatus which I have this day presented to the Alabama Polytechnic Institute in commemoration of the first homecoming of the alumni. The president, the faculty, the alumni , and the student body join me in expressing love and esteem to the father of electrical development.

Miller Reese Hutchinson 7

The set had a limited range; and unless the message was relayed by other operators, it is doubtful that Edison received the well wishes until Hutchinson returned to work.

With the call letters 5YA and a wave length of 1800 meters, a few faculty members and students proudly put the small station on the air. The following year, a course in wireless telegraphy was offered which included code work and fundamental radio principles. 8 The station was operated for several years without a great deal of fanfare or activity. Some modifications of the original equipment were made in order to increase range, and 5YA was heard as far away as Indianapolis, Indiana. 9

World War I brought a national fear of spies and saboteurs with a resulting ban on private wireless operation. The United States Navy took over all the stations it could use, and the remainder were required to shut down and disassemble their transmitters. 10 At Auburn 5YA was dismantled in accordance with the new law, and wireless work was restricted to training operators for the Army. Two limited range, portable sets were used. Issued by the Army, they were housed in small, grey boxes (see Figure 2) . The Army also provided some non-transmitting buzzer devices for teaching code.11 Over 200 wireless telegraph operators were trained at Auburn during the war. 12

One of the Instructors hired by the school to train the soldiers in wireless telegraphy was a young Tampa, Floridian, named Victor Caryl McIlvaine. Born in 1898, McIlvaine had become interested in radio in 1912 after reading a radio catalog which he had found. He had constructed a set and taught himself code by listening to a nearby Marconi station. Later he had obtained a first-grade amateur and a second-grade commercial operator's license. 13

In the summer of 1917, McIlvaine went to sea as an operator for the Marconi Company and for a year traveled about the Gulf of Mexico. In 1918, he was hired by Alabama Polytechnic Institute as a radio instructor for the soldiers in vocational training. He began teaching and attending electrical engineering classes.

After the armistice in November, 1918, McIlvaine decided to stay at Auburn and get an engineering degree. He found himself taking freshman and sophomore courses during his senior year, since he had been permitted to take most of the advanced courses while only a freshman. 14

In 1919, the ban on transmitters was lifted. McIlvaine immediately began building a new code station. All that was left of 5YA was the 150-foot antenna pole, so he used what apparatus he had of his own plus cast-off items he could scrape up from the Electrical Engineering Department and the machine shop. The new station was licensed 5XA, indicating that it was the first experimental station in the fifth radio district. 15

For transmitting, the station had an old Clapp-Eastham Type E one KW transformer, a homemade rotary quenched gap spark unit, a plate glass condenser, and an OT made of one-fourth inch ribbon. 16 The hoisting cable on the Hutchinson antenna pole had deteriorated during the war, so McIlvaine persuaded his roommate, E. F. Sanborn, to shinny up the pole and replace it. On his first attempt, Sanborn reached the first group of guy wires about half-way up. 5XA operated for several weeks with a single wire antenna to this point. Later, Sanborn tried again and by using two loops of rope, one for each foot, and alternately sliding them up the pole, he managed to reach the top . From here a single wire, long-wave antenna was extended to a water tank behind Wright's Drug Store. 17

The school permitted the station to be housed in a small room in the rear of a wooden-framed building near the campus main gate. The remainder of the building was used for chemistry classes. Here the set was gradually improved by making a new OT, obtaining a two KW Packard transformer, salvaging a one-eighth horsepower motor and mounting a hyrad disk on it, immersing the condenser in transformer oil, and purchasing an antenna ammeter. The college permitted all this activity, but no financial assistance was given. 18

The new station began attracting amateur operators, and soon there were enough hams in the Auburn area to keep 5XA on the air almost continuously. A watch schedule was established so someone would be on duty at night. To the little corps of operators the rotary spark gap "made beautiful music and generated a lovely odor of ozone. While someone was sending, you could read the sparks on a power pole at the main gate". 19

As the first person to establish a full-time, professional caliber station at Auburn, McIlvaine is unquestionably the father of Auburn broadcasting.

In 1920, the operators formed the "I Tappa Key Club" (see Figure 1). Meetings were irregular, usually when one of the members got a box of cookies or other treats from home. The only "associate" member was Eleanor Dickinson McIlvaine, wife of V. C. McIlvaine and sister of club member Jack M. Dickinson. She skillfully supplemented the boxes from home with her own cooking. 20

The faculty member with the greatest interest in the hams was Professor A. St. C. Dunstan, affectionately nicknamed "Bull". He taught courses in electrical. engineering and acted as faculty advisor to the group. His son, Arthur ( "Little Bull"), joined the club while still in high school and remained affiliated with the station throughout his college years. 21

At the beginning of the school year 1921-22, the station expanded into an adjoining room. By this time, the hams had accumulated an overflow of electronic equipment, and the old room had become crowded. The various receiving apparatus, a home- made power panel, a one-fourth KW 500 cycle transmitter, and a five-watt CW set were moved into the new room. 22 The main spark transmitters remained in the old room (see Figure 2). The year was spent in continuous radio activity.

The Birmingham News Gift

On March 19, 1922, while 5XA hummed with activity, a new era of Auburn broadcasting began. The Birmingham News, in a front-page story, announced that it was donating $2,500 to Auburn for the purchase of a new voice broadcasting station. 23 The donation was to be part of a $1000,000 fund-raising campaign which Auburn supporters had begun that year. Victor Hanson, editor of The News, had decided to make the newspaper t s contribution specifically for a new station. Auburn alumni, H. W. Brooks and Lonnie Munger, were given credit for originating the idea. Brooks had been a radio operator in the United States Army and, with E. A. Allen and R. D. Spann, had operated the original Hutchinson set while attending Auburn. 24 Mc11vaine and Professor Dunstan traveled to Birmingham and demonstrated a borrowed radio receiver to Mr. Hanson. Voice stations in Detroit (WWJ) and Pittsburgh (KDKA) were tuned in. 25

The Birmingham News publicized the gift for several days , stating that the new station would be as powerful as any in the country and that Auburn would be the fifth college in the nation to have such an installation. 26 A reporter contacted Thomas A. Edison for comment, and in a front-page article, Edison was quoted as having said, "That is fine, fine. I am delighted that a radio broadcasting station of such proportions will be established in a southern university " 27 Thus for a second time, Edison was informed of new radio developments at Auburn University.

The News announced in another story that the purpose for purchasing a broadcasting station for Auburn was to make absolutely certain that nightly programs at Auburn would be available to all parts of Alabama, even under the most unfavorable weather conditions. 28

Dr. Sprite Dowell, Auburn President, publicly regarded the new station as "essential to the proper equipment of a modern technical college. 29 Professor Dunstan was openly enthusiastic. In a statement for The News he said, "The gift of $2,500 to Auburn by The Birmingham News for the purchase of a powerful radio broadcasting outfit spells the elimination of isolation in Alabama. He said that radio programs would be regularly broadcast by the new station, and like the air we breathe, they would be free to any person who would install a radio set to receive them.30

Professor Dunstan's enthusiasm was merited. In 1922, radio transmission of the human voice was still in its infancy The pioneering KDKA in Pittsburgh had made its famous first broadcast only seventeen months earlier, In Alabama only a few people had receiving sets and even fewer had transmitters In March, 1922, there were approximately 125 receiving sets, eleven radio telegraph dispatching stations, and five radio telephone dispatching stations in Birmingham. There were no broadcasting stations anywhere in the state.31 The Alabama Power Company would begin operating WSY in Birmingham on April 24 1922.

Since assembled transmitters were unavailable in those days , the new station at Auburn would have to be homemade. The necessary apparatus was purchased at a discount through Matthews Electrical Supply Company of Birmingham. 32

As the parts began to collect at the Auburn Railroad Depot the University administration initiated a search for the proper place to put a broadcasting station in the school's organizational structure. Since a radio station would extend Auburn University to the people of Alabama, it was decided to make it a function of the Agricultural Extension Service (see Figure 3). Mr. L. N. Duncan, Director of Extension, called on Mr. Posey Oliver Davis in his office in Comer Hall and told him he was to be the new radio station manager. 33

Born on August 15, 1890, at Athens, Alabama, Mr. Davis had attended Potter College at Bowling Green, Kentucky and Auburn University, where he received the B . S. degree in 1916. He had pursued further graduate study at Auburn and began a career in news and public relations work for the Extension Service and Experiment Station. 34

Mr. Duncan told Davis that the school had no money for operating a broadcasting station; but since Mr. Hanson had made

the gifts they were on the spot to do something with it. 35 Later Davis recalled the moment:

So there in about two minutes 1 found myself in charge of a radio broadcasting station in a railroad station. This was where I started and was in it for a dozen difficult years-- always trying to run a creditable broadcasting station in a little town with very limited means, a derth [sic] of talent, and countless problems, some of which turned into headaches and heartaches. 36

Mr. Davis soon would become the key personality in the development of broadcasting at Auburn University. His administrative skill would be a powerful factor in prolonging the station survival.

McIlvaine and the other 5XA operators volunteered their services and went to work assembling the transmitter parts. By the time the station got on the air, the Extension Service had spent much more than $2, 500. There were countless hidden expenses in wiring and furnishing a studio. 37

The new station and 5XA were moved into a room on the second floor at the southeast end of Broun Hall. Four transmitters and the new station were arranged to operate from the same position. They were as follows: (1) a 100-watt CW on 200 meters, (2) a one KW non-synchronous spark on 200 meters, (3) a two KW synchronous spark on 375 meters, (4) a one-fourth quenched gap spark set (ship type) on 200 meters, (5) the new broadcasting station capable of 1500 watts. 38 (see on 200 meters. (Figure 4).

The new broadcasting station required an efficient ground system; so after considerable discussion, the operators decided to construct one using old thirty-gallon tanks. For maximum efficiency, the tanks were cut in half lengthwise, each piece connected to a heavy wire cable, and the entire system buried near Broun Hall. The cable led to the operating room on the second floor. To cut the tanks, McIlvaine and a few of the operators slipped into the electrical engineering lab when no one else was around, started one of the D.C. generators, and used an electric arc. Being unfamiliar with arc cutting, they failed to use a face mask and each became very red—faced. Luckily, no one suffered any eye damage. 39

By the end of the year, a commercial license was granted by the Commerce Department. The assigned call letters were WMAV. McIlvaine created the slogan "Make A Voice" to correspond with the letters. 40

WMAV began broadcasting in November of 1922. The homemade 1500-watt transmitter would never be operated at full power because there was never enough money to get six operable 250- watt tubes together at one time. The tubes were expensive and had very short lives. 41

On February 21, 1923 WMAV formally opened and dedicated. Victor Hanson, Governor Brandon, and Auburn President Dowell made speeches on the air, and the A. P. I. Serenaders provided music. 42As a new extension of the state land-grant university, WMAV was immediately obligated to program regularly for the people of Alabama. The University announces that the station was primarily for weather, market and crop reports. Broadcasting for pure entertainment was to be of a secondary nature. The station began broadcasting weather reports at 10:00 a.m. and 12:00 noon on 480 meters. Market reports soon followed.

As the schedule was enlarged, regular broadcasts were begun at 8:00 p.m. on Thursdays and Saturdays. By this time, the frequency had been shifted to 250 meters.

On Thursday evenings, a musical program was usually offered. Soon after the station had been moved into Broun Hall, a remote microphone was installed in nearby Langdon Hall Auditorium, From here concerts could be picked up for broadcast. 43 The school orchestra and glee club were featured regularly. At other times, instrumental solos and vocalist were scheduled and occasionally someone would make a short speech. 44 Since radio was still a novelty, listeners were delighted to hear anything. On the other hand, the station operators enjoyed using the equipment and would gladly broadcast anyone who could play an instrument.

On Saturday evenings, a farm program was offered. Faculty members in the Agriculture Department made talks on farming practices and market conditions. 45

The increased broadcast activity brought a rather severe acoustical problem to McIlvaine 's attention. Within the buildings, the primitive microphone picked up undesirable reverberations and feedback. McIlvaine never fully solved the difficulty; but by draping velvet around the microphone, he was able to dampen it somewhat. 46

While WMAV's programing slowly expanded, the code station continued handling ever-increasing traffic. as a member of the American Radio Relay League, 5XA provided a radiogram service free of charge to the public. In May, 1923, 5XA handled over 300 messages which entitled it to membership in the Brass Pounder's League. The little station was heard as far away as Canada, Hawaii, and England. 47

As radio technology improved, operators became more sophisticated; but there were still plenty of novices around, Louis Howle, one of the student operators, tried for months to talk via code to California. He sent out calls to many stations, but no answers came back. One night while working the station alone, John McCaa, another student, communicated with six stations in California. Howle was perplexed when he saw the contacts listed in the log the following morning and accused McCaa of an over-active imagination. That night they both went to the station, and Howle again tried to raise several California stations. There were no answers. He turned to McCaa and said, "Now you talk to one." McCaa sat down, and the first station he called answered. The reason, they discovered, was that Howle was calling at twenty words per minute; while McCaa could manage only five words per minute. The stations in California could not copy at the faster speed. 48

As people began buying radio receivers for their homes, the number of WMAV listeners increased. Even before the station was formally dedicated, postcards had been received from twenty-one states. Most of these were nigh-time contacts when atmospheric conditions were favorable. Daytime broadcasting was limited to parts of Alabama and surrounding states. 49

To increase range it was decided to improve the antenna. Dean J. J. Wilmore, Head of the Engineering Department, gave the operators permission to erect a new antenna pole on the roof of Broun Hall. The students cut down a forty-foot pine tree, stripped off the limbs, hoisted it to a prominent place, and strapped it into position. When Dean Wilmore saw the improvised antenna mast, some say he lost all the dignity of his office. 50

An early plan called for locating receivers at county agricultural extension offices so low income rural folk could benefit from the farm programs. The Matthews Electrical Supply Company of Birmingham donated ten receiving sets to the University for this purpose. Total value of the sets was over $2,000. 51 Six of them were located throughout the state, and four were kept at Auburn for teaching and experimental work. Installations were made at Athens, Bay Minette, Dothan, Florence, Greensboro, and Guntersville 52 (see Figure 5) . McIlvaine spent several days

traveling about the state installing these receiving sets. He also began a small business in Auburn with a classmate, H. S. Brownell. They sold homemade radio receivers. The lowest priced model sold for $8.75. 53

WMAV continued broadcasting until 1925. McIlvaine was graduated in 1923, giving up his position as radio instructor and chief operator. J. M. Wilder, a student instructor in radio, took charge of WMAV, and L. W. Howle took over 5XA. 54

The Alabama Power Company Gift

On April 24, 1922, the Alabama Power Company began operating, the first radio broadcasting station in Alabama. Its call letters were WSY, and it was located on Powell Avenue in downt0wn Birmingham. The station was soon moved into the Loveman, Joseph, and Loeb Department Store. A studio was built in the store's radio shops and an antenna was mounted on the roof. 55

By the fall of 1923, the power company decided that it could no longer continue to support the station. The cost of hiring talent for programs became excessive. On November 6 1923, WSY broadcast its final evening of entertainment. 56 The station then remained dormant for over a year.

Early in 1925, at the suggestion of Victor Hanson, the Alabama Power' Company donated WSY to Auburn. 57 The station was dismantled, shipped to Auburn, and reassembled by the radio students . Wilder was in charge of the operation. He was sent to Memphis, Chicago, Cincinnati, and Atlanta to get first-hand information on the proper method of installation. 58

The new station was transmitting within a few months. The old WMAV call letters were retained.

Despite the gift of WSY, the station was already obsolete. Very little progress was being made. Through the country a "radio boom" was on. Stations with strong financial backing were coming to the forefront. WMAV was not keeping pace

FOOTNOTES

- Head, Broadcasting in America, 126.

2. Orange and Blue, September 28, 1912, p. 3.

3. A. M. Dunstan, "Radio Station Had Small Beginnings, The Auburn Engineer, I (April, 1926) , 7.

4. Orange and Blue, September 28, 1912, p. 3.

5. Ibid

6. "The Hutchinson Wireless Station Auburn Alumnus , 11 (August, 1913) , 17.

7. Ibid.

8. "Course in Wireless Telegraphy at Auburn Next Year," Auburn Alumnus, 111 (August, 1914) , 13.

9. Dunstan, The Auburn Engineer, (April, 1926) , 7.

10 Head, Broadcasting in America, 104.

11 Interview with V. C. McIlva1ne, September 15, 1968.

12 Dunstan, The Auburn Engineer, (April, 1926) , 7 .

13 V. C. McIIvaine, "Radio Station 5XA, T' East Gulf Radiogram (May, 1922) , 13.

14 Interview with V. C. McIlvaine, September 15, 1868.

15 Letter from V, C. -McIlvaine to author, August 16, 1968.

16 McIIvaine, East Gulf Radiogram, (May, 19 22) , 150

17 Interview with Jack M. Dickinson, September 15, 1968.

18 McIlvaine, East Gulf Radiogram, (May, 1922) , 16.

19 Letter from Albert E. Duran to author, July 23, 1968.

20 Interview with V. C. McIlvaines September 15, 1968.

21 Letter from L. W. Howle to author, July 22, 1968.

22 McIlvaine, East Gulf Radiogram, (May, 1922) , 16.

23 The Birmingham Newsy March 19, 1922 p. 1.

24 The Birmingham News, March 20, 1922, p.1.

25 Orange and Blue, March 25, 1922, p.1 .

26 The Birmingham News , March19, 1922, p.1.

27 The Birmingham News , March 22, 1922, p.1.

28 'The Birmingham , News, March 19, 1922, p.1.

29 Ibid.

30 The Birmingham News , March 20, 1922, p.1.

31 The Birmingham News , March.19, 1922, p.1.

32 Orange and Blue, March 25, 1922, p.1.33

33 Letter from P. O. Davis to Dr. Ralph Draughon, November 25, 1961.

34 Frank L. Grove, Library of Alabama Lives (Hopkinsville, Ky. : Historical Record Association, 1961) , p. 143.

35 Letter from P. O. Davis to Dr. Ralph Draughon, November 25, 1961.

36 Ibid.

37 Ibid

38 Letter from Albert E. Duran to author, July 23, 1968.

39 Interview with V. C. McIlvaine September 15, 1969.

40 Ibid.

41 Ibid.

42 The Plainsman, March 14, 1924, p. 1.

43 Interview with V. C. McIlvaine, September 15 1968.

44 The Plainsman, March 14, 1924, p. 1.

45 Ibid.

46 Letter from J. J. Duncan to author, July 26, 1968.

47 The Plainsman, December 7 , 1923, p. 1.

48 Letter from John McCaa to author, July 29 , 1968.

49 The Plainsman, November 29, 1922, p. 1.

50 Letter from L. W. Howle to author, July 22, 1968.

51 The Birmingham News, March 26, 1922, p. 1.

52 The Birmingham News, February 3, 1923, p. 1.

53 The Plainsman, November 18, 1922, p. 2.

54 Letter from L. W. Howle to author, July 22, 1968.

55 Thomas W. Martin, The Story of Electricity in Alabama (Birmingham: Birmingham Publishing Company, 1952) p. 78.

56 Ibid.

57 J. M. Wilder, "Radio Station W.A.P.I" The Auburn Engineer , I (October, 1925) , 7.

58 The Plainsman, January 31, 1925, p. 1.

III. THE BIRTH OF WAPI

The Decision to Stay in Broadcasting

By the mid-1920 's, a "radio boom" had stimulated interest throughout the nation. Coupled with the general optimism of post-World War I America, radio's financial future seemed very bright indeed. Technological advances were making last month 's new receiving set obsolete, The advertising dollar was demanding larger audiences through better programs.

In 1920, Edwin Armstrong had patented the superheterodyne circuit, a revolutionary development which had vastly increased the sensitivity of home receiving sets. By 1924, superheterodyne radios were in general use, bringing an end to the need for outside antennas. 1 By the mid-twenties, crystal detectors, headphones and batteries were on the way out. All were rapidly being replaced by reliable vacuum tubes, loud speakers, and receivers which would operate on standard household current.

To keep pace with the burgeoning new field, in 1924 the Electrical Engineering Department at Auburn added an advanced course in broadcast engineering theory. The new course also included basic work in vacuum tubes. 2

By current standards, radio programming in the mid-twenties was incredibly nonsensical, inartistic and boring; but broadcast audiences in those days had not reached a very high level of sophistication. However, by the late twenties, news, drama, and radio personalities had become emerging forces in the new medium. All three were supported by a strong backbone of music.

In 1925, Auburn University's homemade, hand-me-down transmitter continued limited service to the farmers of southeast Alabama. Daytime range was disappointing to Mr. Davis and his small staff. The station could hardly be heard outside the county. 3 Mr. Davis feared that radio would have to be dropped from the Extension Service program. He realized that, if he didn't push the issue, WMAV would soon die an obsolescent death. Aside from the few student engineers on the radio staff, Davis received no faculty support for his broadcast activities. A1ready, he had found it difficult to program volunteer lecturers from the University. No one was interested in gratis work. 5

Two alternatives became clear: junk WMAV and forget about broadcasting, or buy new equipment to keep up with the field. Mr. Davis favored the latter. He was convinced that a power increase would revitalize the station. Dr. L. N. Duncan, Director of Extension, supported Davis, since he had asked him to get into broadcasting in the first place. 6 The final decision was made by the Board of Trustees of the University on. June 1, 1925. Upon recommendation of President Sprite Dowell, the board authorized the rebuilding of the station "in accordance with plans prepared by members of the college staff and that the necessary expenditures be authorized from Extension Service funds." 7 At the same meeting, the board directed that the new station be named the "Victor Hanson Broadcasting Station of the Alabama Polytechnic Institute." 8

The decision of the Board of Trustees to continue the station committed Auburn to many long, frustrating years of broadcasting. But a bit of pride was involved. After all, the school had been a radio pioneer in 1912 and in 1922. Giving up in 1925 would be rather embarrassing.

A contract was made with the Western-Electric Company for a new one KW transmitter. 9 The new unit cost the Extension Service about $40,000. 10 A Western-Electric representative assured Mr. Davis that the new transmitter would deliver a clear signal to a radius of 135 miles. 11 Davis was delighted. The future looked bright. Now Auburn 's Electronic Extension Service would be heard over most of southern Alabama.

When the new transmitter arrived, the radio staff immediately began installation. A small concrete block transmitter shack was built on the Agriculture Department grounds south of the campus 12 (see Figure 6). Remembering the difficult days with WMAV, the engineers went to great lengths to avoid doing anything that would hamper the new station's range. Care was taken to locate the transmitter shack away from interference creating power poles and buildings. All communications and electrical lines running to the transmitter control panel were buried. Only high quality, shielded cable was used through the new system. 13

At the time of the new transmitter purchase, the old WMAV station had expanded into several new rooms in Broun Hall. The original second floor room which had been occupied by the earlier Birmingham News station had been converted into a studio. Drapes and padding had been added to improve the acoustics. On the first floor a power plant supplied the necessary voltages with a motor generator, three phase power supply, batteries, and charging equipment. 15

The main operating room, containing a power panel, control panel, and speech input amplifier, was located on the third floor. Here the engineer on duty could control the first floor power units and the frequency generating equipment. A loud-speaker was used to monitor output. 16 Early plans called for incorporating all this equipment into a new system by stringing transmission and communication lines out to the new transmitter: but the old equipment fell into disuse and was eventually dismantled. 17

Comer Hall became the new Auburn radio center. Located on a knoll just south of the main campus, Comer Hall was the focal point of the agricultural school. Into this alien environment came the electrical engineers with their microphones, tubes, and wires. A new studio was installed in a top floor room of the building. 18 The room was completely draped with sound deadening material-both walls and ceiling. The floor was covered with Ozite and this in turn was covered with a rug. The complete acous tical treatment made the room absolutely "dead." Mr. Davis described the sensation of announcing in the studio as "like speaking into a feather bed." The accoustical treatment was so complete that later it had to be modified. During a trip to New York, Mr. Davis was told by NBC officials that it was preferable to have a studio with a little "life" in it. They gave Mr. Davis a formula which he put into effect upon returning to Auburn. The formula called for a ninety per cent sound absorbing ceiling, sixty per cent sound absorbing walls, and a hard floor. 20

The Commerce Department granted a license to the new station under the Radio Act of 1912, which was still in effect. Mr. Davis, remembering that the station was an extension of the University, requested the call letters WAPI. The school was named the Alabama Polytechnic Institute at the time. Since no other station held those letters, the request was granted. 21

WAPI began broadcasting on 248 meters. The formal opening was held on the evening of February 22, 1926. The program included speeches by W. W. Brandon, Governor of Alabama; Sprite Dowell, Auburn President; and Victor Hanson, editor of The Birmingham News. The governor spoke on "Station WAPI and Alabama." Dr. Dowell gave the history and purpose of the station, and Victor Hanson spoke on "Radio and the Press."

Music for the occasion was supplied by the Auburn Radio Orchestra. The members of the orchestra were Mrs. Sarah M. Tidmore, piano; Mrs. Mary D. Askew, violin; Paul Fontille, saxophone; Dick Yorbrough, saxophone; James Leslie, cornet; L. B. Halman, Jr., trombone; Slick Molton, banjo; and Toby Morgan, drums. 23

Mrs. Tidmore recalled opening night:

They didn't have a tape recorder in those days, so programs were done live. We were scared to death that everything wouldn't go right. Our little orchestra didn't want to make any big mistakes on the first night. As I recalls everything went smoothly. 24

The opening program of WAPI was heard in many parts of the nation and numerous congratulatory telegrams and letters were received. 25

In order that radio listeners in Birmingham could hear the broadcast, the evening program at WBRC, a Birmingham station, was postponed until 8:30 p .m. Both WBRC and WAPI were broadcasting on 248 meters. Following the speeches and music from Auburn, WBRC came on the air with Uncle Bud Grayson and his Uke1e1e, Nappi 's Orchestra, and Oliver Sims with his Harmonica. 26

The two stations arranged their nighttime schedules to avoid mutual interference. 27

WAPI began broadcasting practically every day except Sunday, averaging approximately ten hours of air time per week. Several frequency shifts were made to avoid interference with other stations. After a three week of silence in September 1926 the station returned to the air with a frequency of 461.3 meters.

Chaotic conditions existed in broadcasting at this time. In a legal case (Hoover, Secretary of Commerce vs. Intercity Radio Co. , Inc. 286 F. 1003, at 1007, 1923) and in a following opinion of the Attorney General of the United States, the regulatory power of the Department of Commerce had been stripped away. 30 Stations were shifting frequencies at will. The resulting bedlam moved Congress to pass the Radio Act of 1927. Before the situation was stabilized by the new Act, Auburn's one-kilo- watt voice was lost in the jumble.

Programming in the Twenties

In 1920, the mere sound of a voice crackling through a set of headphones was enough to give even the most reticent listener chills of excitement. What was being said was unimportant. The fascination of a strange voice coming right out of the ether was enough. Then actual events of national interest were broadcast, the excitement became fever pitched. In 1921, several programming firsts aroused great interest. The first boxing event to be broadcast occurred on April 113 1921. The program originated from Motor Square Garden in Pittsburgh. 31 Four -months later, KDKA reported the Davis Cup Matches for the first time. Other firsts came swiftly after.

By 1922, it was clear that, despite the special coverage of sports and news events, the backbone of broadcasting was music. If there was nothing else to do, the engineer could always turn on the phonograph. The early, regularly scheduled radio programs were mostly musical with bits of patter between numbers.

Erik Barnouw, in his book Tower in Babel, described broadcast music of the twenties as "potted palm music" after the plant which must have decorated practically every studio in America. In his book, Barnouw describes the music's flavor:

It was the music played at tea time by hotel orchestras. It was recital music. European in origin, it was culture to many Americans . It was part of the heritage that thousands of musicians, amateur and professional, had brought with them from the old world, and was to thig extent a typical feature of the new world experience. Seeking the new, the immigrant clung to the symbols of the old. This music completely dominated radio in its first years and retained a leading role throughout the twenties . 33

By 1927, a host of lavish musical programs vied for audiences. The Cliquot Club Eskimos, the Ipana Troubadours, and the Eveready Hour brought popular music into American home. 34 The classical and semi-classical concerts of the "potted palm" era were slowly losing their dominance.

Radio personalities emerged in the late twenties. Listeners had come to expect and enjoy a familiar voice; Graham McNamee' s made him famous. His thrilling description of the 1927 Rose Bowl Game was carried over the first coast-to- coast hook-up. Alabama played Stanford to a seven-to-seven tie.

Radio drama appeared early but failed to become popular until the thirties. On August 3, 1922, WGY Players performed in the broadcast of Eugene Walter's The Wolf. This probably

til the thirties . On August 3, 1922, the WGY Players performed in a broadcast of Eugene Walter's The Wolf. This was probably the first full-length drama production on radio. By April 1924 the WSY Players were being heard via network connection in New York and Washington. 37

Although it would take global conflict to bring radio news broadcasting to full flower, the twenties saw a few attempts at broadcasting journalism. Newspaper-owned stations began broadcasting "bulletins" as teasers to stimulate readers. 38 Only years later would radio be fully appreciated as a news medium.

Educational institutions had begun broadcasting classes for credit as early as September 1923. For four years, the Massachusetts University Extension offered a total of twenty-one courses via station WBZ. 39 Haaren High School in New York City broadcast an accounting course in 1923. 40 Kansas State Agricultural College began courses for credit in 1925. General psychology, sociology, English literature, and economics were some of the areas of study offered. 41

As one might suspect, much of the programming by WAPI was agricultural in nature, but like most stations across the country it heavily relied upon a firm foundation of music, The small studio orchestra was depended upon to supply thick slices of music on command. When the band was unavailable, the engineers would select a record and fire up the studio phonograph. 42

Most of the members of the orchestra were students, and many times their classes, homework or other extracurricular activities would interfere with the program schedule. Mrs. Tidmore and Mrs. Askew spent many evenings hanging out the studio windows nervously looking up the street for approaching band members and hoping enough would arrive before air time. 43

The usual procedure was for everyone to arrive about thirty minutes before going on the air to decide what songs would be played that evening. The band would read the fan mail which had come in from the previous broadcast to see if there were any requests. A few numbers might get a quick rehearsal, but usually the first run-through was on the air. 44

Live broadcasting had its humorous moments; and John McCaa, who played banjo during the years 1925-1926, recalled one of them;

. . . one night we had a request for a popular number. Everyone could play it, but no one knew the words . I was selected to sing the words, so 1 propped the music up in a chair where I could read the words while playing. Everything was going fine till, when about half through, a strong breeze came through the windows and blew the music across the room. I just broke out laughing as did the others. The confusion lasted for about five minutes before we got back to playing again. Our mail from that program was more than usual, and of all things, people asked us to repeat that program as they had enjoyed our "skit." 45

R. D. Yorbrough got a similar surprise from WAPI audience.

He wrote,

One afternoon I was playing a piano solo - "Some of these Days" I got carried away I started singing the words . To my amazement, the station got a number of cards and letters requesting an encore. I complied. I have a nondescript singing voice and nobody in their right mind would ask me and nobody in their right mind would ask me to sing, and I haven't volunteered since. 46

The studio orchestra at the beginning of the 1926-1927 school had picked up several new members. Mrs. Mary Drake Askew still played violin, and Miss Mary Elizabeth Motley of Montgomery played piano. Other band members were Paul Fontille, saxophone; Dick Yorbrough, saxophone; Leven Fosters cornet; John McCaa, banjo; and F. W. Perkins, drums.

Other orchestras also made regular appearances on WAPI. The Auburn Collegians, a jazz band, benefited greatly from their radio performances and made numerous personal appearances across the state. 48 Elmer Overton's and Tommy Jones' bands made several appearances on programs. 49

One night in November, 1926, the Atlanta and West Point Railway Band was featured. A twelve-year-old singer named Chester Wickersham Kitchen was on the same program. 50

The soloists, choral groups, and bands, which trooped through the studio of WAPI, are too numerous to mention. The station simply had little else to offer but music of a distinctive southern "potted palm " variety.

The non-musical programs were mostly lectures and must have been quite boring. Weekly reports of an egg-laying contest, book reviews, and religious discussions are typical examples and probably had very small followings. Some other examples of the kinds of talk shows offered are: a report by Professor G. D. Sturkle on the rotation plots at Auburn. 51 A talk by Professor F. E. Guyton on how to get rid of cockroaches and a Sunday school lesson by Professor J. R. Rutland. About the only regular talk show featured was Dr. George Petrie's Current Events lectures. 54 At no time in WAPI's history were any courses offered for credit. 55

The cultural extremes broadcast by WAPI would amuse the radio listener of today. The modern listener has become accustomed to specialized radio; programs are uniformly designed to appeal to specific audiences. Not so with WAPI. Opera could follow farming tips; a book review might precede dance music. On November 3, 1926, student members of the Auburn Wilsonian Literary Society could have established the high point of cultural broadcasting at WAPI. The student newspaper reported that the program "demonstrated to the radio public of Alabama that Auburn did have a few students interested in literary work." 56

Only three weeks earlier "Uncle Timothy" Gowder had won five dollars for being the champion hog-caller in the Agriculture Club. The contest was broadcast over WAPI. A man in Columbus, Georgia that his radio set had been close to the window; and when the contest began , his neighbor's hogs broke out. 57

Based on fan mail received, the most popular programs offered by WAPI in the twenties were the sport broadcast. 58 Auburn football and baseball games had been carried on WMAV, and the practice was continued on WAPI. Remote pickup wires were strung to Drake Field and games were broadcast play-by-play (See Figure 8). As soon as a game was over, the expensive wire had to be quickly gathered up and stored away; otherwise, long sections would mysteriously disappear. 59

When WAPI carried the World Series of 1926, listener response was overwhelming. During one game, forty-nine long distance telephone calls and thirteen telegrams were received. 60 Several hundred letters filled with expressions of gratitude and praise arrived the following week (See Figure 9).

Actually, the Series was not broadcast live. A teletype circuit was installed, and announcer Bill Young read the play-by-play report off the wire. 61 During the last game a listener in Columbus, Georgia called the station and offered Mr. Young a new hat if his team won. Young announced the offer on the air; and before the game was over, he had received enough

promises for a complete winter wardrobe. A druggist called and said he would give Young a bar of soap for washing his new clothes. This was broadcast, producing an offer of towels. An undertaker called and offered a secondhand casket. Another responded with a shroud. 62 To Bill Young, the afternoon was an enlightening look at the power of radio advertising.

One of the last big programs to be broadcast over WAPI at Auburn was an appeal for alumni support carried on the evening of April 18, 1929. Dr. L. N. Duncan, Mr. P. O. Davis, Dr. George Petrie, and other faculty members and alumni made speeches. Plans for Alumni Day, May 20, 1929, were announced. 63

During the early twenties, Auburn could boast of programs comparable with any station in the United States. Only during the last few years of the decade did it become apparent that listeners were no longer tuning in WAPI. Only the sports events were drawing respectable audiences. More power would not be enough. Something else would have to be done to get the listeners back.

The Difficulties at Auburn

The Western-Electric transmitter had made little improvement in WAPI's range. During the day, effective range was only thirty miles. 64 At night a greater radius could be reached, but listeners had to tune their receivers very carefully. Hundreds of stations were crowding the broadcast band. Picking WAPI out of the jumble became extremely difficult. The average listener would not even try, preferring to tune in louder stations on the dial.

With the creation of a new Federal Radio Commission in 1927, a period of relative stability began. Auburn was assigned a new frequency of 340.7 meters or 880 kilocycles . Unfortunately the same frequency was assigned to WJAX in Jacksonville, Florida; and a time-sharing schedule had to be worked out to avoid mutual interference. Two stations in Kansas City, Kansas, also operated on an assigned 880 kilocycles; 67 but they were far enough away not to cause problems.

Again, Mr. Davis and his small staff became discouraged (see Figure 10). Davis saw the station suffering from obvious deficiencies - small audiences and little talent. To increase the audience, he again considered a power boost. If the station was easy to hear, maybe more people would tune in. The last expensive power increase had been a disappointment. He feared another one might produce the same result. 68 Besides, the new Federal Radio Commission had become concerned about the crowded frequency spectrum; and a request for more power would probably be denied. Yes, this time more than just power was involved.

By 1928, Mr. Davis also had become aware that the small town of Auburn could not supply enough talent to satisfy the voracious appetite of radio programming . A network affiliation

seemed to be the best answer. With an affiliation, much of the programming could come from New York where there was plenty of talent. When Mr. Davis approached NBC officials with his idea, they immediately turned him down.

They laughed at me. They told me that there weren't enough people in southeast Alabama to make expensive line rental practical. I came back to Auburn wondering how WAPI would be able to compete with the popular network shows. 69

Clearly, WAPI was again dying.

FOOTNOTES

- Head, Broadcasting in America, 103.

- Plainsman, October 31, 1924, p.1.

- Interview with P.O. Davis, October 16, 1968

- Letter from P.O. Davis to Dr. Ralph Draughon, November 25, 1961

- Interview with P.O. Davis, October 16, 1968

- Letter from P.O. Davis to Draughon, November 25, 1961

- Minutes of the Board of Trustees, Auburn University, Vol IV, June 1, 1925, p.158

- Ibid.

- P. O. Davis, "Alabama Poly Unfolds Big Radio Idea, The Auburn Alumnus, X (December, 1928) , 4.

- Interview with P. O. Davis, October 16, 1968.

- Letter from P . O. Davis to Dr. Ralph Draughon, November 25 , 1961.

- Ibid..

- J. M. Wilder, "Radio Station W.A.P.I.," the Auburn Engineer, I (October, 1925), 7.

- Ibid. , p. 16.

- Ibid. p. 7.

- Ibid.

- Interview with P . O. Davis, October 16, 1968.

- Wilder, The Auburn Engineer, (October, 1925) 16.

- Interview with P. O, Davis, October 16, 1968.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- The Birmingham News, February 23, 1926, p. 1.

- Ibid.

- Interview with Mrs. Sarah M. Tidmore, October 18, 1968.

- The Birmingham News, February 23, 1926, p. 1.

- The Birmingham News, February 22, 1926, p. 1.

- Interview with P. O. Davis, October 16, 1968.

- Davis, The Auburn Alumnus, (December, 1928) , 4.

- Plainsman, September 24, 1926, p. 1.

- Head, Broadcasting in America, 128.

- Gleason L. Archer, History of Radio to 1926 (New York: The American Historical Society, Inc., 1938), 212

- Ibid. , p. 213.

- Barnouw, p. 126.

- Ibid. , p. 191.

- Sam J. Slate and Joe Cook, It Sounds Impossible (New York: The Macmillan Co., 1963) , p. 54.

- Barnouw, p. 136.

- Ibid. , p. 137.

- Ibid., p. 138.

- Armstrong Perry, Radio Education (New York: The Junior Extension University Press, 1929), p.39.

- Ibid. , p. 41.

- Ibid. , p. 45.

- Interview with P. O. Davis, October 16, 1968.

- Interview with Mrs. Sarah M. Tidmore, October 18, 1968.

- Interview with P. O. Davis, October 16, 1968.

- Letter from John McCaa to author, July 29, 1968.

- Letter from R.D. Yorbrough to author, July 29, 1968.

- The Plainsman, September 24m 1926, p. 1.

- Letter from L. W. Foster to author, August 5, 1968.

- Letter from R.D. Yorbrough to author, July 29, 1968.

- The Plainsman , November 20, 1926, p. 6.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- The Auburn Alumnus, IX (February, 1928) , 37.

- Interview with P. O. Davis, October 16, 1968

- Ibid.

- The Plainsman, November 6, 1926, p. 1.

- The Plainsman, October 16, 1926, P. 3.

- Interview with P. O. Davis, October 16, 1968

- Ibid.

- The Plainsman, October 9, 1926, p. 1.

- The Plainsman, October 16, 1926, p. 2.

- Ibid.

- "Auburn Alumni Radio Program Presented Over WAPI," The Auburn Alumnus, X (April, 1929) , 8.

- Interview with P. O. Davis, October 16, 1968

- Ibid.

- Annual Report of the Federal Radio Commission to the Congress of the United States for the Year Ending June 30, 1928, (Washington; U.S. Government Printing Office, 1928). p/88.

- Ibid. , p. 75.

- Interview with P. O. Davis, October 16, 1968.

- Ibid.

BROADCASTING IN BIRMINGHAM

WAPI is Moved

Mr. P. O. Davis pondered the future of WAPI. Returning alone from a business trip to Montgomery, he found himself searching for answers. 1 He knew the station had been a failure. Hidden away in the southeast corner of the state, it was far from any heavily populated area. The financial drain on the Extension Service had been unexpected. Only a few hours a week could be filled with the limited, local talent. The programs were poor, and few faculty members were willing to help. The problems seemed insurmountable.

Suddenly, Davis hit upon an idea. Why not move the station to the talent, audience, and support rather than trying to operate the other way around? The largest city in Alabama was Birmingham. If WAPI could be moved there an audience would be guaranteed. Then NBC might reconsider and offer the station an affiliation contract. Even without network help, WAPI would surely have the pick of hundreds of talented Birmingham gingers and musicians, all anxious to get on the air. With another power boost, all Alabama would be served, since Birmingham was almost in the center of the state. 2

Again Mr. Davis took a new idea to Dr. L. N. Duncan, Director of the Extension Service. Again, he received Duncan's support. They decided a move to Birmingham and a power boost from one to five kilowatts might make WAPI something it could never be at Auburn. Davis and Duncan took their plan to Auburn President Bradford Knapp. He agreed. 3

P. O. Davis was in Birmingham the next day with a proposal. Auburn would install a five-kilowatt station in Birmingham and provide half the annual operating costs up to $20,000 if the City of Birmingham would match the $20,000 and pay half the cost of installation. The operation of the station was to be left in the hands of the school. 4

Mr. Davis later wrote, "After a sales talk of a few minutes, Mayor Jimmy Jones agreed to the $20,000; and the way was clear for action. 5

Final approval was given by the University Board of Trustees on May 21, 1928. Dr. Duncan went before the board and explained the reasons for a move and the financial arrangement possible with the city. The board gave President Knapp full power to act after conferences with the Executive Committee. 6

An agreement with. the City of . Birmingham quickly followed (see Appendix A) ; and at the August 3, 1928, meeting of the Board of Trustees, a motion to pay for the cost of transfer from Extension Service funds was adopted. A total of $30,000 was to be paid immediately. The board also authorized the negotiation of loans to cover the remaining transfer costs. The loans were not to exceed $75,000 at a rate of interest no greater than six per cent per annum. Half of the sum borrowed was to be repaid within one year from the date of the loan and the remaining half within two years. 7

Work on the new station began in September, 1928. Seven and a half acres of land near Sandusky, Alabama, were purchased from the Tennessee Coal, Iron, and Railway Company. 8 Here, a building thirty-two by forty-eight feet was constructed for the new transmitter. The two 200-foot steel towers which had been in service at Auburn were disassembled, shipped to the location, and installed. No other parts of the old WAPI were moved to Birmingham. 10 The old one-kilowatt transmitter at Auburn was sold to the Gillette Rubber Company of Eau Claire, Wisconsin for $7,500. The unit's new call letters became WTAQ. 11

A new ground system covering an area 400 by 600 feet was buried at the site near Sandusky. 12 At the time, it was estimated that the new station would have a signal strength ten times greater than the old Auburn station. Modernized broadcasting apparatus was credited for the improvement. 13

The new transmitter was a Western-Electric, type 105-C, five-kilowatt unit 14 (see Figure 11) . An operator's control desk faced the transmitter, and a communications hookup with the main studio was nearby. The transmitter site was approximately seven miles from downtown Birmingham. 15

The new studios were located on the top floor of the Protective Life Building at the corner of First Avenue and Twenty-First Street in Birmingham. The Protective Life Insurance Company provided space for two studios (see Figure 12) , a control room (see Figure 13) , reception room, and offices. 16 In turn, the station agreed to make occasional announcements telling where its studios were. 17 In 1928, any business firm was anxious to have a radio station in its building. The publicity was excellent and free.

P. O. Davis had favored the Tutwiler Hotel as the studio location; but pressure was applied by Victor Hanson, who held stock in the Protective Life Company.18 Since Hanson had been largely responsible for the first voice station at Auburn and had the old WAPI named in his honor, his desires prevailed.

As work on the new WAPI neared completion, a contract was made with the Southern Bell Telephone Company for long distance transmission lines between Auburn, Montgomery, and Birmingham. Under the terms of the contract, Southern Bell was to receive $1,000 per month for line rental. A suitable line existed between Montgomery and Birmingham, but a new one had to be installed between Auburn and Montgomery to complete the hookup.19 With these long distance lines, programs could originate from the old Comer Hall studios at Auburn and from the State Department of Agriculture and Industries in Montgomery. 20

Early plans called for broadcasting six hours each week from Auburn and Montgomery, five hours during the day and one hour at night. During a one-hour daytime show, the State Department of Agriculture and Industries was to present market news first, followed by more news from Auburn. The one hour per week of nighttime broadcasting was to originate entirely at Auburn. 21

Rates for a normal one-hour telephone hookup would have been considerably less than $1,000 . If only talking circuits had been used and if the line had not been connected directly with the microphone at Birmingham, the rate would have been $116.40 per month from Montgomery to Birmingham and $70.80 per month from Montgomery to Auburn. This was the rate for a one-hour period from noon until 1:00 p.m. daily, except Sunday. 22 However, recent Federal Radio Commission rulings had upheld the practice of charging higher rates when the line was directly connected to broadcast apparatus. 23

On December 27, 1928, the first tests of the new station began. From 2:00 a.m. until approximately 6 : 00 a.m., the equipment was warmed up and checked. These early morning checks continued until the official opening program on December 31, 1928. 24

The chief engineer for the Birmingham station was J. M. Wilder. After six months, Wilder left and was replaced by A. E. Duran. Duran stayed with the station until Februarys 1931. 25

The New Year's Eve formal opening was heard by thousands throughout Alabama and the Southeast. Within a week, over three thousand congratulatory letters had been received. While the opening program was on the airs telegrams and phone calls from twenty-one 0ne states poured in. 26

Again, WAPI was forced to Share time with another station. This time it was KVOO in Tulsa, Oklahoma. At 7:55 p.m. KVOO signed off announcing that the frequency was being turned over to WAPI at 8:00 p.m. WAPI began the festivities with bugle calls and the national anthem played by the Boys' Industrial Band of Birmingham. 27

Speeches were made by Bibb Graves, Governor of Alabama; J. M. Jones, President of the Birmingham City Commission; Bradford Knapp, President of Auburn; L. N. Duncan, Director of the Extension Service at Auburn; Victor Hanson, Publisher of The Birmingham News and Age Herald; W. D. Bishop, President of the Jefferson County Board of Revenue; S. F. Clabaugh, President of the Protective Life Insurance Company; P. O. Davis , General Manager of WAPI; and H. C. Smith of the State Department of Agriculture. 28

Four guest announcers were imported from other southern stations to help out at the microphone. They were George Dewey Hay , " The Solemn Old Judge" of WSM, Nashville, Tennessee; G. C. Arnoux, "The Man With the Musical Voice" of KTHS, Hot Springs, Arkansas; Luke Lee Roberts of WLAC, Nashville, Tennessee; and J. C. "Bud" Connelly of WBRC, Birmingham. 29

The WAPI announcers were Walter N. Campbell, new manager of WAPI, and W. A. Young, assistant manager. 30

The program lasted until 4:00 a.m. "The Voice of Alabama" had been born.

Broadcasts from Montgomery and Auburn began approximately one month later. A special type of wire was needed to connect the Auburn studio. The wire had to be ordered, causing a delay.32

The Montgomery studio was in the building occupied by the Department of Agriculture and Industries. The Jesse French and Sons Piano Company offered a parlor grand piano for the Montgomery studio, but most of the broadcasts from there were agricultural reports. 33

An Alliance Among Schools

The grand opening of WAPI attracted the attention of George H. Denny, President of the University of Alabama. He immediately became interested in radio and sent Dr. Ben Wooten, Head of the University's Physics Department, to Washington to see the Federal Radio Commission about a license for a station in Tuscaloosa. Dr. Wooten also traveled to New York to see National Broadcasting Company officials and visit several radio stations 34.